I recently perused the book Typewriter Art: A Modern Anthology by Barrie Tullett and was introduced to concrete poetry. As those who study and create concrete poetry will tell you, it’s hard to neatly define what concrete poetry is. Sometimes, it’s best defined by the ways it differs from traditional lyric poetry. Concrete poetry often, but not always, abandons the structure of neat lines that form neat stanzas and purposefully interacts with the physical space of the page. In other cases, concrete poetry resists linearity and is about the web of connections among the words, syllables, or letters on the page. Concrete poetry can be many things all at the same time, so let’s jump into an example:

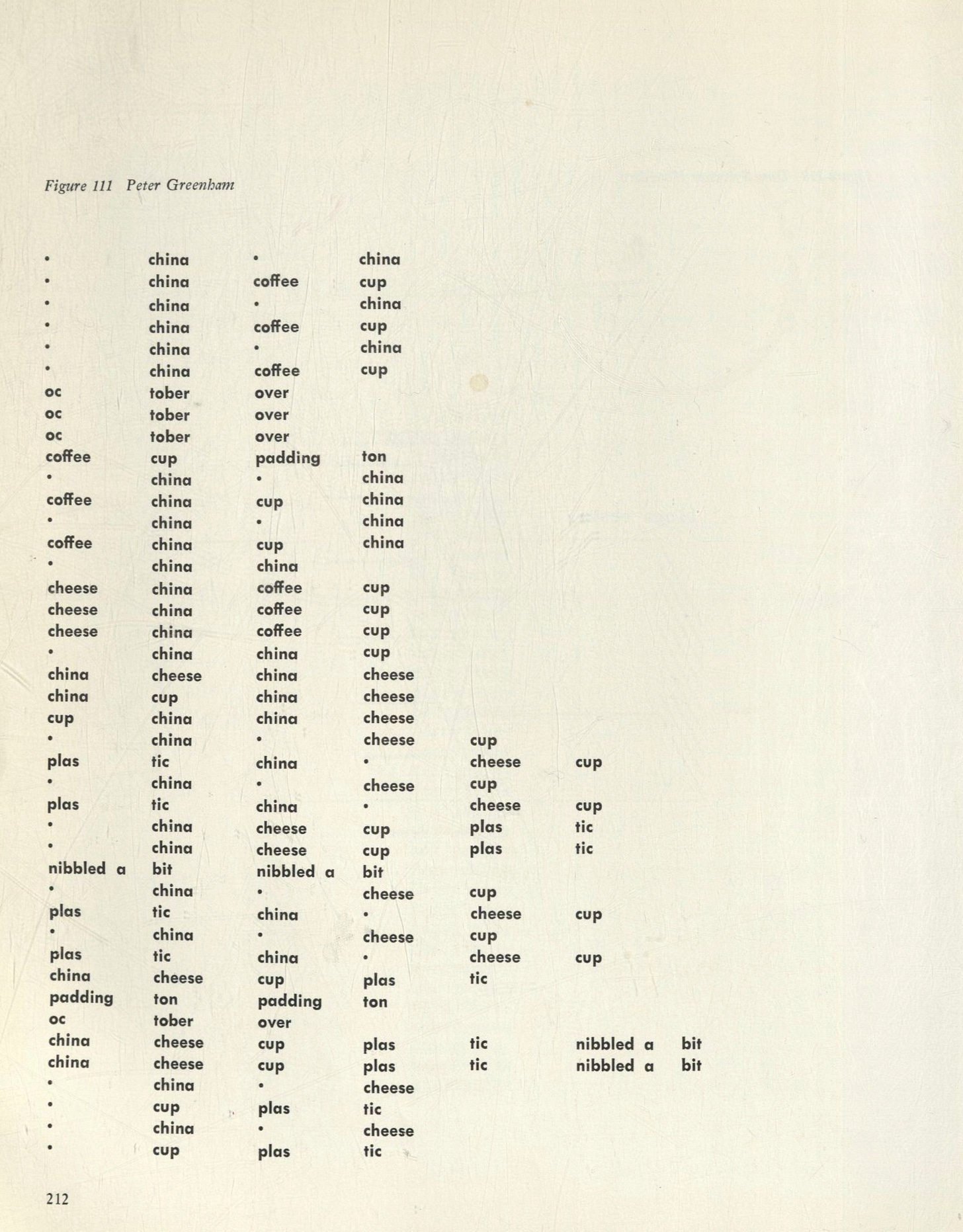

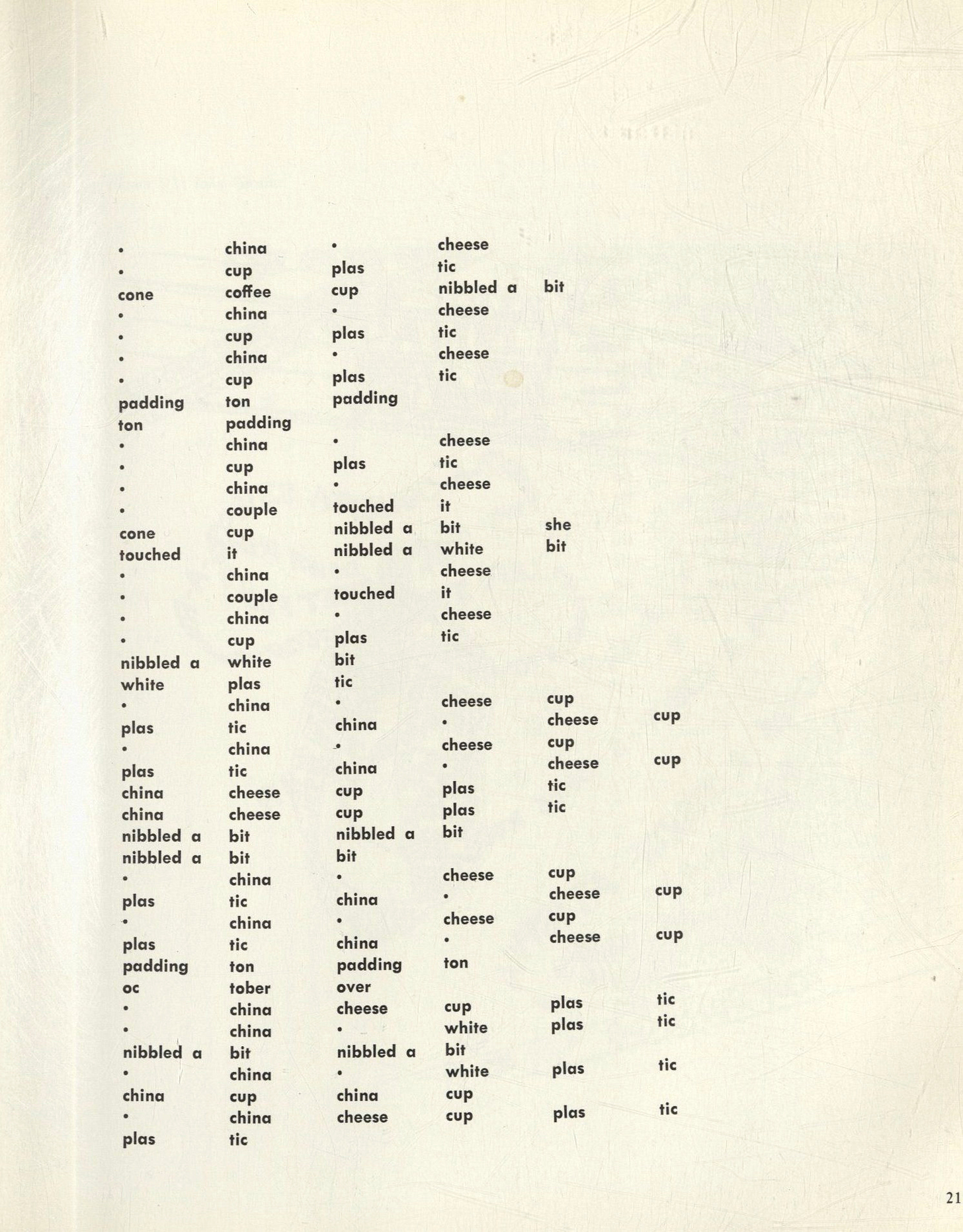

Above is an untitled work by Peter Greenham, an English poet known for his musical concrete poetry. The collection this poem appears in notes that Greenham’s (not to be confused with Greenegg’s) work is “A sound rhythm poem. Each line is divided into from 1 to 7 beats as indicated by the dots (silence) and words.” Indeed, setting a metronome and performing this poem aloud is an edifying way to spend ten minutes or so. The “ch” sounds in “china” and “cheese” are emphasized compared to the softer “plas” and “padding” sounds. “tic,” “oc,” and “cup” are staccato - they’re single syllables hit shortly and sharply1. The silences introduce anticipation and syncopation, making it sound a bit stilted. Greenham creates a musical score of sorts but one in which the score itself is a work of visual art.

Like lots of other music, Greenham relies on repeated phrases interrupted by variation followed by a return to the repeated phrase. Sometimes these phrases are modified with different words tagging along. These patterns are easy to miss on first glance. Greenham insists that we pay close attention. But finally, he hammers his point home with persistent repetitions of “china cup plas tic.”

Visually, the work is composed of neat columns, but their lengths vary creating peaks and valleys on the poem’s right edge. They introduce a sense of flow and visual interest. At times, we’re tempted to compress certain columns, for surely “plas” and “tic” ought to be together and the same for “oc” and “tober.” Greenham skillfully uses space to sonically play with words and manipulate their sounds to fit his musical vision. The visual form of this work is inseparable from its musical form.

“cheese” in this poem contributes to the “ch” sound motif, and it is one of the few nouns that has a verb associated with it. Cheese gets “nibbled a bit” at various points throughout the poem. This is the only consumption we witness and almost the only action. Musically, “cheese” is a word we can stretch out with its sustained “ee” sound in the middle. It’s a touch of legato amidst the staccato. The sonic qualities match the physical properties of stretchy cheese, like warm mozzarella you can pull apart. I’m inclined to think, then, that Greenham isn’t writing about hard cheese.

But what does the damn thing mean? With all the sonic playfulness, it’s clear the poem is meant to evoke a sensory response. Putting that together with the meanings and connotations of Greenham’s words requires an act of imagination. Many of his words point me towards the description of a tea party, yet the contrast of “china” with “plastic” complicates things. Is the party fancy or not? I think the party and its guests try to be. The party-goers “nibble” on cheese, putting on their best, most restrained manners. They drink coffee out of their cups whether they are made of china or not. The party and its guests are masquerading as something they’re not, and the discomfort is apparent in the poem’s music. The sounds are stop and start, with the sharp, staccato notes imitating clinking cups or silverware atop an obvious lack of conversation. Visually, too, the columns resemble guests standing at a polite yet uncomfortable distance.

What is so engaging to me about concrete poetry is that it requires the reader to integrate different types of input - sound, visual layout, diction - to get at its meaning. To be fair, I don’t think I found the meaning here, but I was inspired to think and imagine, a result good poetry should aspire towards.

[Untitled Concrete Poem by Peter Greenham appears in Concrete Poetry: A Worldview edited by Mary Ellen Solt, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, IN, 1968.]